Email

info@lml.org.ph

Remnants: Per Pacem et Libertatem

When the artillery fire of the United States of America and Japanese forces obliterated the buildings of what Filipinos today know as Old Manila, underneath the rubble, among the bodies, were remnants of paintings. A considerable number of 19th century works housed in government buildings and within homes of the upper crust of Philippine society were lost in the Battle of Manila. Among them was a large mural by Felix Resurreccion Hidalgo: Per Pacem et Libertatem (For Peace and Liberty). A painting that in its neoclassical glory told of the supposed peace with the United States would, some forty years later, be destroyed by the guns of the same nation.

Before it found its way to Manila, Per Pacem et Libertatem was first exhibited in the St. Louis World Fair of 1904. The world fair boasted of several exhibitions, structures and waterways, all spectacles to encourage wonder. The works of art from the Philippines were segregated from the main hall of paintings located at the Art Palace. It was magnificent structure surrounded by undulating fountains that glimmered under the sun. The structure consisted of a Central Building as the hall of exhibitions for American painters; the East and West pavilions for “Foreign Exhibits;” and a separate Sculpture Court for said art form. Not among the “Foreign Countries” category, the Philippines was meant to be displayed in a reservation away from declared nations.

Hidalgo’s twenty four canvases were among six hundred thirty four Filipino works that were shipped to the United States to be hung within the forty acre Philippine reservation. The canvases were displayed at the ground floor of the Government Building within the land allotted for the Philippine exhibition. The same building housed the offices of the Philippine Exposition Board which sat comfortably at the second floor of the two-story building. Familiar names were exhibited along with Felix Resurreccion Hidalgo; among them: Juan Luna, Miguel Zaragosa, Fabian dela Rosa, etc.

Sign Up For An Account

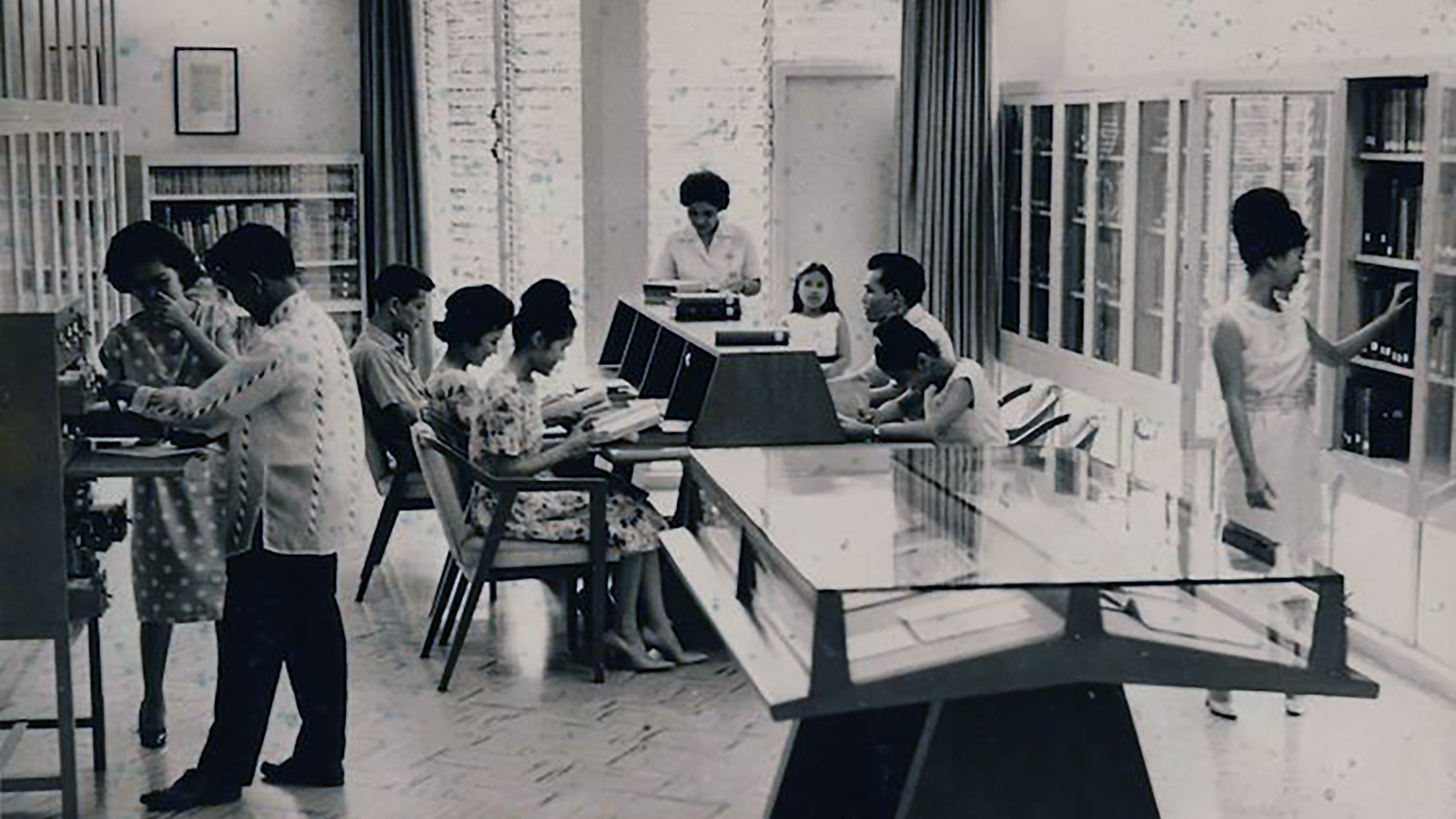

The Lopez Museum and Library is the oldest privately owned and managed museum and library specializing in Philippine material.

Sign Up